Our Beliefs

The Christian church’s birth was at Pentecost, as described in the Book of Acts. At Pentecost the Jewish disciples of Jesus proclaimed the Gospel to people of many cultures and languages. By the middle of the first century, the church was made up of Jewish and Gentile believers who worshiped God, in the name of Jesus Christ, in the power of the Holy Spirit. The church began to grow rapidly throughout the region we now know as the Middle East, even through hardship and persecution from the Roman Empire.

During the fourth century, after more than 300 years of persecution under various Roman emperors, the church became established as a political as well as a spiritual power under the Emperor Constantine. The church became strong in the east (Greek-speaking) and the west (Latin-Speaking) regions of the Roman Empire and beyond. Among the greats of the east was Athanasius and among the greats of the west was Augustine. Eventually the western portions of Europe came under the religious and political authority of the Roman Catholic Church. Eastern Europe and parts of Asia came under the authority of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

During the Middle Ages a number of mystics emerged, including Julian of Norwich, who have shaped the spirituality of many Christians.

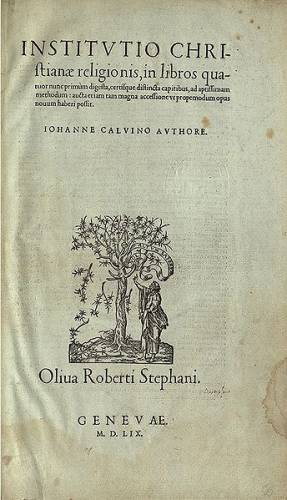

In western Europe, the authority of the Roman Catholic Church remained largely unquestioned until the Renaissance in the 15th century. The invention of the printing press in Germany around 1440 made it possible for common people to have access to printed materials including the Bible. This, in turn, enabled many to discover religious thinkers who had begun to question the authority of the Roman Catholic Church. One such figure, Martin Luther, a German priest and professor, started the movement known as the Protestant Reformation when he posted a list of 95 grievances against the Roman Catholic Church on a church door in Wittenberg, Germany, in 1517. Some 20 years later, a French/Swiss theologian, John Calvin, further refined the reformers’ new way of thinking about the nature of God and God’s relationship with humanity in what came to be known as Reformed theology. John Knox, a Scotsman who studied with Calvin in Geneva, Switzerland, took Calvin’s teachings back to Scotland. Other Reformed communities developed in England, Holland and France. The Presbyterian church traces its ancestry back primarily to Scotland and England.

Log College Building

Presbyterians have featured prominently in United States history. The Rev. Francis Makemie, who arrived in the United States from Ireland in 1683, helped to organize the first American Presbytery at Philadelphia in 1706. In 1726, the Rev. William Tennent founded a ministerial “log college” in Pennsylvania. Twenty years later, the College of New Jersey (now known as Princeton University) was established. Other Presbyterian ministers, such as the Rev. Jonathan Edwards and the Rev. Gilbert Tennent, were driving forces in the so-called “Great Awakening,” a revivalist movement in the early 18th century. One of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, the Rev. John Witherspoon, was a Presbyterian minister and the president of Princeton University from 1768-1793.

In the early years of the 19th century, the movement known as the Second Great Awakening began around the celebration of Presbyterian communion services. This movement spread rapidly and gave birth to the camp meeting movement in the United States. Presbyterians became more of a town church in this period as small towns began to grow in the previously rural areas.

In the early 20th century the Presbyterian vision for church and ministry was crystalized in the Six Great Ends of the Church: the proclamation of the gospel for the salvation of humankind; the shelter, nurture, and spiritual fellowship of the children of God; the maintenance of divine worship; the preservation of the truth; the promotion of social righteousness; and the exhibition of the Kingdom of Heaven to the world.

Presbyterian denominations in the United States have split and parts have reunited several times starting in the 18th century. Currently the largest Presbyterian denomination is the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), which has its national offices in Louisville, Ky. It was formed in 1983 as a result of reunion between the Presbyterian Church in the U.S. (PCUS), the so-called “southern branch,” and the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A. (UPCUSA), the so-called “northern branch.” This reunion has been a bright spot of reconciliation and unity in the history of American Presbyterianism. Other Presbyterian churches in the United States include the Presbyterian Church in America, the Cumberland Presbyterian Church, the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, ECO (A Covenant Order of Presbyterians), and the Associate Reformed Presbyterian Church.

The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) is governed by its Constitution, the Book of Order and The Book of Confessions.

The history of the Presbyterian Church is taken from the PC(USA) website here.

Some of the principles articulated by John Calvin are still at the core of Presbyterian beliefs. Among these are the sovereignty of God, the authority of Scripture, justification by grace through faith and the priesthood of all believers. What these tenets mean is that God is the supreme authority throughout the universe. Our knowledge of God and God’s purpose for humanity comes from the Bible, particularly what is revealed in the New Testament through the life of Jesus Christ. Our salvation (justification) through Jesus is God’s generous gift to us and not the result of our own accomplishments. It is everyone’s job — ministers and lay people alike — to share this Good News with the whole world. That is also why the Presbyterian church is governed at all levels by a combination of clergy and laity, men and women alike.

Presbyterians confess their beliefs through statements that have been adopted over the years and are contained in The Book of Confessions. These statements reflect our understanding of God and what God expects of us at different times in history, but all are faithful to the fundamental beliefs described above. Even though we share these common beliefs, Presbyterians understand that God alone is lord of the conscience, and it is up to each individual to understand what these principles mean in his or her life.

Advent

Angels

Apostles’ Creed: Jesus Descended into Hell

Art

The Ascension

The Ascension II

The Atonement

Authority: Who’s in charge in the congregation?

Baptism

Baptism II

The Bible

The Bible — The Living Word

Biblical Interpretation

Biblical Justice

‘Community’ redefined in view of COVID-19

Communion

Confessions

Connectional Church

Connectional Church: Grace, Gratitude, Risk-Taking Service

Connectional Church: Networking

Creation and Nature

Deacons

The Devil

Ecclesia Reformata…

Ecumenism

Elders

Embracing Change

End of Life Issues

The End of the World

Epiphany

Eschatology

Evangelism

Evil

(Don’t) Believe

A Brief Statement of Faith

Faith and Patriotism

Forgiveness

Grace

Hell

Hell II

Hell: ‘Jesus Descended into Hell’ (Apostles’ Creed)

Heresy

How to Speak Presbyterian

Infant Baptism (2006 version)

Infant Baptism (1985 version)

Interfaith Relations

Jesus

Jesus II

Jesus Is Lord

Holy Spirit

Holy Spirit (3 Views)

Life After Death

Lord of the Conscience

Love

Mary

Mary: how Jesus’ mother reflects God’s love

Miracles

Nature and Creation

Ordination

Prayer and the Korean Church

Predestination

Predestination II

Priesthood of All Believers

Priesthood of All Believers II

“Prosperity Gospel”

Purity

Reconciliation

“Reformed and Always Reforming”

The Resurrection of Jesus I

The Resurrection of Jesus II

Sacraments

Second Coming

Sin and Salvation

Spirituality

Stewardship

The Trinity

Reclaiming the Trinity

Vocation

Wealth

Who Are We as Presbyterians?

Worship

The information from this page was taken from the PC(USA) website here.

“In gratitude to God, empowered by the Spirit, we strive to serve Christ in our daily tasks and to live holy and joyful lives, even as we watch for God’s new heaven and new earth praying, ‘Come, Lord Jesus.’” —From “A Brief Statement of Faith”

At the core of Presbyterian identity is a secure hope in the grace of God in Jesus Christ, a hope that, by the power of the Holy Spirit, empowers us to live lives of gratitude: “In affirming with the earliest Christians that Jesus is Lord, the Church confesses that he is its hope, and that the Church, as Christ’s body, is bound to his authority and thus free to live in the lively, joyous reality of the grace of God.” (Book of Order F-1.0204)

This strong emphasis on the grace of God in Jesus Christ is our heritage from the founder of the Reformed tradition, John Calvin.

Presbyterians

What is unique about the Presbyterian Church?

What’s Presbyterian worship like?

Sacraments

Infant Baptism

Predestination

Women in the Church

Becoming a Presbyterian minister

Presbyterians are distinctive in two major ways. They adhere to a pattern of religious thought known as Reformed theology and a form of government that stresses the active, representational leadership of both ministers and church members.

What are human beings created to do? Reformed theology says that human beings are to “know God and enjoy [God] forever.” Theology is a way of thinking about God and God’s relation to the world. Reformed theology evolved during the 16th century religious movement known as the Protestant Reformation.

In its confessions, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) expresses the faith of the Reformed tradition. Central to this tradition is the affirmation of the majesty, holiness and providence of God who creates, sustains, rules and redeems the world in the freedom of sovereign righteousness and love. Related to this central affirmation of God’s sovereignty are other great themes of the Reformed tradition:

• The election of the people of God for service as well as for salvation.

• Covenant life marked by a disciplined concern for order in the church according to the Word of God.

• A faithful stewardship that shuns ostentation and seeks proper use of the gifts of God’s creation.

• The recognition of the human tendency to idolatry and tyranny, which calls the people of God to work for the transformation of society by seeking justice and living in obedience to the Word of God. (Book of Order, G-2.0500)

A major contributor to Reformed theology was John Calvin, who converted from Roman Catholicism after training for the priesthood and in the law. In exile in Geneva, Switzerland, Calvin developed the Presbyterian pattern of church government, which vests governing authority primarily in elected members known as elders. The word Presbyterian comes from the Greek word for elder.

A major contributor to Reformed theology was John Calvin, who converted from Roman Catholicism after training for the priesthood and in the law. In exile in Geneva, Switzerland, Calvin developed the Presbyterian pattern of church government, which vests governing authority primarily in elected members known as elders. The word Presbyterian comes from the Greek word for elder.

Elders are chosen by the people. Together with ministers of the Word and Sacrament, they exercise leadership, government, and discipline and have responsibilities for the life of a particular church as well as the church at large, including ecumenical relationships. They shall serve faithfully as members of the session (Book of Order, G-10.0102). When elected as commissioners to higher governing bodies, elders participate and vote with the same authority as ministers of the Word and Sacrament, and they are eligible for any office (Book of Order, G-6.0302).

The body of elders elected to govern a particular congregation is called a session. They are elected by the congregation and in one sense are representatives of the other members of the congregation. On the other hand, their primary charge is to seek to discover and represent the will of Christ as they govern. Presbyterian elders are both elected and ordained. Through ordination they are officially set apart for service. They retain their ordination beyond their term in office. Ministers who serve the congregation are also part of the session. The session is the smallest, most local governing body. The other governing bodies are presbyteries, which are composed of several churches; synods, which are composed of several presbyteries; and the General Assembly, which represents the entire denomination. Elders and ministers who serve on these governing bodies are also called presbyters. Presbyteries and synods are also collectively referred to as mid councils.

Worship in a Presbyterian congregation, in its shape and content, is determined by the pastor and the session, the church’s governing body. It generally includes prayer, music, Bible reading and a sermon based upon Scripture, prayers of intercession, personal response/offering, and the Sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

The constitution of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) suggests that worship be ordered in terms of four major actions centered in the revelation of Jesus Christ: Gathering, Word, Sacrament, and Sending.

Prayer. “Prayer is at the heart of worship. It is a gift from God, who desires dialogue and relationship with us. It is a posture of faith and a way of living in the world. Prayer is also the primary way in which we participate in worship. Christian prayer is offered through Jesus Christ and empowered by the Holy Spirit. Faithful prayer is shaped by God’s Word in Scripture and inspires us to join God’s work in the world.

There are many kinds of prayer—adoration, thanksgiving, confession, supplication, intercession, dedication. There are many ways to pray — listening and waiting for God, remembering God’s gracious acts, crying out to God for help, or offering oneself to God. Prayer may be spoken, silent, sung, or enacted in physical ways” (W-2.0202).

Music. “The singing of psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs is a vital and ancient form of prayer. Singing engages the whole person, and helps to unite the body of Christ in common worship. The congregation itself is the church’s primary choir; the purpose of rehearsed choirs and other musicians is to lead and support the congregation in the singing of prayer. Special songs, anthems, and instrumental music may also serve to interpret the Word and enhance the congregation’s prayer. Furthermore, many of the elements of the service of worship may be sung. Music in worship is always to be an offering to God, not merely an artistic display, source of entertainment, or cover for silence.” (W-2.0202).

Scripture.“The Scriptures bear witness to the Word of God, revealed most fully in Jesus Christ, the Word who ‘became flesh and lived among us’ (John 1:14). Where the Word is read and proclaimed, Jesus Christ the living Word is present by the power of the Holy Spirit. Therefore, reading, hearing, preaching, and affirming the Word are central to Christian worship and essential to the Service for the Lord’s Day.

Scripture.“The Scriptures bear witness to the Word of God, revealed most fully in Jesus Christ, the Word who ‘became flesh and lived among us’ (John 1:14). Where the Word is read and proclaimed, Jesus Christ the living Word is present by the power of the Holy Spirit. Therefore, reading, hearing, preaching, and affirming the Word are central to Christian worship and essential to the Service for the Lord’s Day.

A minister of the Word and Sacrament is responsible for the selection of Scriptures to be read in public worship. Selected readings are to be drawn from both Old and New Testaments, and over a period of time should reflect the broad content and full message of Scripture. Selections for readings should be guided by the rhythms of the Christian year, events in the world, and pastoral concerns in the local congregation. Lectionaries ensure a broad range of biblical texts as well as consistency and connection with the universal Church” (W-3.0301).

Preaching. “A sermon, based on the Scripture(s) read in worship, proclaims the good news of the risen Lord and presents the gift and calling of the gospel. Through the sermon, we encounter Jesus Christ in God’s Word, are equipped to follow him more faithfully, and are inspired to proclaim the gospel to others through our words and deeds. The sermon may conclude with prayer, an ascription of praise, or a call to discipleship. In keeping with the ministry of Word and Sacrament, a teaching elder† ordinarily preaches the sermon.

Other forms of proclamation include song, drama, dance, visual art, and testimony. Like the sermon, these are to illuminate the Scripture(s) read in worship and communicate the good news of the gospel. When these forms of proclamation are employed, worship leaders should connect them with the witness of the Scripture(s) to the Triune God” (W-3.0305)

Intercession. In response to the Word, we pray for the world God so loves — joining Christ’s own ministry of intercession and the sighs of the Spirit, too deep for words. These prayers are not the work of a single leader, but an act of the whole congregation as Christ’s royal priesthood. We affirm our participation in the prayer through our ‘amen’ and other responses” (W-3.0308)

Offering. “Christian life is an offering of one’s self to God. In the Lord’s Supper we are presented with the costly self-offering of Jesus Christ for the life of the world. As those who have been claimed and set free by his grace, we respond with gratitude, offering him our lives, our spiritual gifts, and our material goods. Every service of worship shall include an opportunity to respond to Christ’s call to discipleship through self-offering. The gifts we offer express our stewardship of creation, demonstrate our care for one another, support the ministries of the church, and provide for the needs of the poor” (W-3.0411).

Sacraments. “The Sacraments are the Word of God enacted and sealed in the life of the Church, the body of Christ. They are gracious acts of God, by which Christ Jesus offers his life to us in the power of the Holy Spirit. They are also human acts of gratitude, by which we offer our lives to God in love and service. The Sacraments are both physical signs and spiritual gifts, including words and actions, surrounded by prayer, in the context of the Church’s common worship. They employ ordinary things—the basic elements of water, bread, and wine — in proclaiming the extraordinary love of God. The Reformed tradition recognizes the Sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper (also called Eucharist or Holy Communion) as having been instituted by the Lord Jesus Christ through the witness of the Scriptures and sustained through the history of the universal Church” (W-3.0401).

Denominations often differ over what they recognize as sacraments. Some recognize as many as seven sacraments, others have no sacraments in the life of the church. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) has two sacraments, baptism and the Lord’s Supper.

“The first Christians, following Jesus, took three primary elements of life—water, bread, and wine—as symbols of God’s self-offering to us and our offering of ourselves to God. We have come to call them Sacraments: signs of God’s gracious action and our grateful response. Through the Sacraments of Baptism and the Lord’s Supper, God claims us as people of the covenant and nourishes us as members of Christ’s body; in turn, we pledge our loyalty to Christ and present our bodies as a living sacrifice of praise” (W-1.0204).

Baptism. “Baptism is the sign and seal of our incorporation into Jesus Christ. In his own baptism, Jesus identified himself with sinners—yet God claimed him as a beloved Son and sent the Holy Spirit to anoint him for service. In his ministry, Jesus offered the gift of living water. Through the baptism of his suffering and death, Jesus set us free from the power of sin forever. After he rose from the dead, Jesus commissioned his followers to go and make disciples, baptizing them and teaching them to obey his commands. The disciples were empowered by the outpouring of the Spirit to continue Jesus’ mission and ministry, inviting others to join this new way of life in Christ. As Paul wrote, through the gift of Baptism we are ‘dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus’ (Rom. 6:11)” (W-3.0402).

Baptism. “Baptism is the sign and seal of our incorporation into Jesus Christ. In his own baptism, Jesus identified himself with sinners—yet God claimed him as a beloved Son and sent the Holy Spirit to anoint him for service. In his ministry, Jesus offered the gift of living water. Through the baptism of his suffering and death, Jesus set us free from the power of sin forever. After he rose from the dead, Jesus commissioned his followers to go and make disciples, baptizing them and teaching them to obey his commands. The disciples were empowered by the outpouring of the Spirit to continue Jesus’ mission and ministry, inviting others to join this new way of life in Christ. As Paul wrote, through the gift of Baptism we are ‘dead to sin and alive to God in Christ Jesus’ (Rom. 6:11)” (W-3.0402).

“Baptism enacts and seals what the Word proclaims: God’s redeeming grace offered to all people. Baptism is at once God’s gift of grace, God’s means of grace, and God’s call to respond to that grace. Through Baptism, Jesus Christ calls us to repentance, faithfulness, and discipleship. Through Baptism, the Holy Spirit gives the Church its identity and commissions the Church for service in the world” (W-3.0402).

“The water used for Baptism should be from a local source, and may be applied with the hand, by pouring, or through immersion” (W-3.0407).

“God’s faithfulness to us is sure, even when human faithfulness to God is not. God’s grace is sufficient; therefore Baptism is not repeated. There are many times in worship, however, when we may remember the gift of our baptism and acknowledge the grace of God continually at work in us. These may include: profession of faith; when participating in another’s baptism; when joining or leaving a church; at an ordination, installation, or commissioning; and at each celebration of the Lord’s Supper” (W-3.0402).

“As there is one body, there is one Baptism. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) recognizes all baptisms by other Christian churches that are administered with water and performed in the name of the triune God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” (W-3.0402).

Lord’s Supper. “The Lord’s Supper (or Eucharist) is the sign and seal of our communion with the crucified and risen Lord. Jesus shared meals with his followers throughout his earthly life and ministry—common suppers, miraculous feasts, and the covenant commemorations of the people of God. Jesus spoke of himself as the bread of life, and the true vine, in whom we are branches. On the night before his death, Jesus shared bread and wine with his disciples. He spoke of the bread and wine as his body and blood, signs of the new covenant and told the disciples to remember him by keeping this feast. On the day of his resurrection, Jesus made himself known to his disciples in the breaking of the bread. The disciples continued to devote themselves to the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, prayers, and the common meal. As Paul wrote, when we share the bread and cup in Jesus’ name, ‘we who are many are one body’ (1 Cor. 10:17)” (W-3.0409).

Lord’s Supper. “The Lord’s Supper (or Eucharist) is the sign and seal of our communion with the crucified and risen Lord. Jesus shared meals with his followers throughout his earthly life and ministry—common suppers, miraculous feasts, and the covenant commemorations of the people of God. Jesus spoke of himself as the bread of life, and the true vine, in whom we are branches. On the night before his death, Jesus shared bread and wine with his disciples. He spoke of the bread and wine as his body and blood, signs of the new covenant and told the disciples to remember him by keeping this feast. On the day of his resurrection, Jesus made himself known to his disciples in the breaking of the bread. The disciples continued to devote themselves to the apostles’ teaching, fellowship, prayers, and the common meal. As Paul wrote, when we share the bread and cup in Jesus’ name, ‘we who are many are one body’ (1 Cor. 10:17)” (W-3.0409).

“The Lord’s Supper enacts and seals what the Word proclaims: God’s sustaining grace offered to all people. The Lord’s Supper is at once God’s gift of grace, God’s means of grace, and God’s call to respond to that grace. Through the Lord’s Supper, Jesus Christ nourishes us in righteousness, faithfulness, and discipleship. Through the Lord’s Supper, the Holy Spirit renews the Church in its identity and sends the Church to mission in the world” (W-3.0409).

“When we gather at the Lord’s Supper the Spirit draws us into Christ’s presence and unites with the Church in every time and place. We join with all the faithful in heaven and on earth in offering thanksgiving to the triune God. We reaffirm the promises of our baptism and recommit ourselves to love and serve God, one another, and our neighbors in the world” (W-3.0409).

“The opportunity to eat and drink with Christ is not a right bestowed upon the worthy, but a privilege given to the undeserving who come in faith, repentance, and love. All who come to the table are offered the bread and cup, regardless of their age or understanding. If some of those who come have not yet been baptized, an invitation to baptismal preparation and Baptism should be graciously extended.

Worshipers prepare themselves to celebrate the Lord’s Supper by putting their trust in Christ, confessing their sin, and seeking reconciliation with God and one another. Even those who doubt may come to the table in order to be assured of God’s love and grace in Jesus Christ” (W-3.0409).

“The Lord’s Supper shall be celebrated as a regular part of the Service for the Lord’s Day, preceded by the proclamation of the Word, in the gathering of the people of God. When local circumstances call for the Lord’s Supper to be celebrated less frequently, the session may approve other schedules for celebration, in no case less than quarterly. If the Lord’s Supper is celebrated less frequently than on each Lord’s Day, public notice is to be given at least one week in advance so that all may prepare to receive the Sacrament” (W-3.0409).

The Bible declares that God claimed humanity as God’s own “before the foundation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4).

The Bible declares that God claimed humanity as God’s own “before the foundation of the world” (Ephesians 1:4).“Both believers and their children are included in God’s covenant love. The baptism of believers witnesses to the truth that God’s gift of grace calls for our grateful response. The baptism of our young children witnesses to the truth that God claims people in love even before they are able to respond in faith. These two forms of witness are one and the same Sacrament” (W-3.0402).

Though a person may be baptized at any age, infant baptism is a common practice in the Presbyterian Church. Parents bring their child to church, where they publicly declare their desire for that child to be baptized. When an infant or child is baptized the church commits itself to nurture the child in faith. When adults are baptized they make a public profession of faith.

“The Sacrament of Baptism holds a deep reservoir of theological meaning, including: dying and rising with Jesus Christ; pardon, cleansing, and renewal; the gift of the Holy Spirit; incorporation into the body of Christ; and a sign of the realm of God. The Reformed tradition understands Baptism to be a sign of God’s covenant. The water of Baptism is linked with the waters of creation, the flood, and the exodus. Baptism thus connects us with God’s creative purpose, cleansing power, and redemptive promise from generation to generation. Like circumcision, a sign of God’s gracious covenant with Israel, Baptism is a sign of God’s gracious covenant with the Church. In this new covenant of grace God washes us clean and makes us holy and whole. Baptism also represents God’s call to justice and righteousness, rolling down like a mighty stream, and the river of the water of life that flows from God’s throne” (W-3.0402).

Presbyterians do not require a person to be entirely immersed in water during baptism; the water may be administered by lifting with the hand or pouring from a vessel. Baptism is received only once. Its effect is not tied to the moment when it is administered, for it signifies the beginning of life in Christ, not its completion. The Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) believes that persons of other denominations are part of one body of Christian believers; therefore, it recognizes and accepts baptisms by other Christian churches.

“Baptism is ordinarily celebrated on the Lord’s Day in the gathering of the people of God. The presence of the covenant community bears witness to the one body of Christ, into whom we are baptized. When circumstances call for the administration of Baptism apart from public worship, the congregation should be represented by one or more members” (W-3.0402).

The information in this section was taken from the PC(USA) website and can be found here.

One of the places where the church has had the opportunity to live up to its proclamations for the equality of all persons is in the status that it gives women in its own life and work.

One of the places where the church has had the opportunity to live up to its proclamations for the equality of all persons is in the status that it gives women in its own life and work.

Although women were first ordained as elders in one of the predecessor denominations to the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) in 1930, it was not until 1956 that presbyteries were permitted to ordain women to the ministry.

In a different predecessor denomination, the 1956 General Assembly approved changes in the church’s constitution to allow the election of women as deacons and ruling elders. Those changes were defeated by the presbyteries, but the 1957 General Assembly responded to the defeat by urging that women be included in all church committees including those on finances and budget. The first ordination of women as elders in this denomination actually occurred in 1962. As ministers, women were ordained beginning 1965.

In 1971, the General Assembly sent overtures to its presbyteries providing for election to church offices in all governing bodies, “giving attention to a fair representation of both the male and female constituency” (Minutes of the 183rd General Assembly (1971), United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A., pp. 305-306).

(Adapted from the Compilation of PC(USA) Social Witness Policies).

The information in this section was taken from the PC(USA) website and can be found here.